With 50 years at the Royal Academy of Music and an international teaching career, Professor Christopher Elton has gained unique experience in how to coach accomplished artists. In this unique interview for Piano Street, Elton shares his insights and views on the big perspective.

People within the professional piano community know his name, and most have heard his students on concert stages around the world and in recordings. For those knowledgeable about piano competitions, he is a household name, and despite retiring 14 years ago, he continues to be active as a teacher and as a judge worldwide. Born in Edinburgh, Christopher Elton received his musical education at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where he earned the Academy’s highest performing award on both piano and cello. He has won several British and international piano competitions, performing as a soloist and in chamber music, and freelanced as a cellist with London orchestras. Elton is renowned internationally for the success of his students at the Royal Academy of Music, many of whom have won prestigious awards in various competitions. He has also conducted masterclasses and served as a jury member in countries around the world, including the USA, Japan, Israel, and China. Additionally, he has given recitals in several countries. For 24 years, Elton was Head of Keyboard at the Royal Academy of Music, and he also held the title of Professor of the University of London. In 2018, he was appointed Visiting Professor of Piano at the University of Yale.

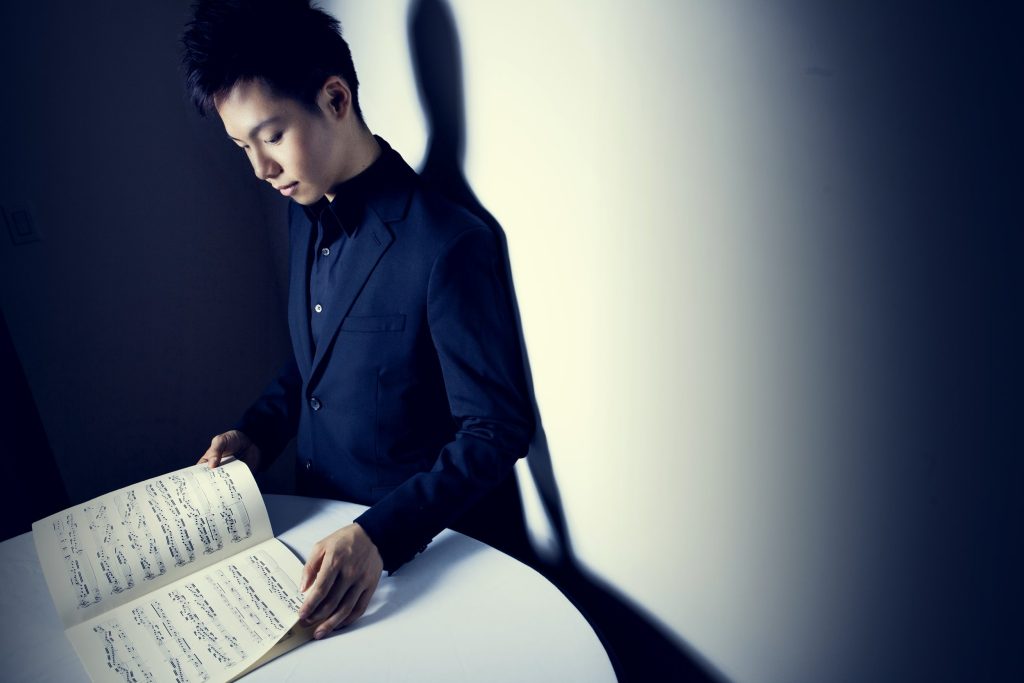

During the 2nd International Piano Competition in Gothenburg 2023, where Piano Street’s Patrick Jovell was part of the jury alongside Professor Elton, the opportunity was given to discuss Elton’s long career and experiences in jury work, both in smaller competitions and the larger, more prestigious ones such as The Cliburn or the Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow. Elton has also a long history with the piano competition in Ettlingen where many famous pianists have distinguished themselves at a young age, such as Lang Lang, Boris Giltburg, Igor Levit, Eric Lu, and Yeol Eum Son to name a few. Elton is a person with a passion for politics and language and nourished aspirations of becoming a barrister if not attending the Academy in his youth. Although Elton regrets not possessing a strong singing voice, his musical abilities suggest a universal and diverse musical knowledge gained from his extensive international experiences.

Patrick Jovell: During our meeting in Gothenburg, I brought up how your vast perspective on things has always stood out to many. Specifically, I referenced your 50+ years of work at the Royal Academy as an example of the longevity of your experiences. I know you retired as Head of Faculty in 2011, but that you are still continuing your teaching there.

Christopher Elton: Well, I greatly enjoyed my work as Head of Keyboard, but sometimes it gets a bit much, and it felt good to be able to focus solely on my teaching. And in Joanna MacGregor I knew I had a fine musician to succeed me in the post. She is so much more the person for a profession that has changed so much since 1987! Competitions are something that I really enjoy because they provide a fresh perspective and allow me to hear new and unique individuals. Additionally, it provides me with opportunities to meet like-minded individuals on judging panels and my colleagues. I don’t really care about the size or scope of the competition, whether it’s modest or extravagant like The Cliburn or Moscow’s Tchaikovsky. That said I do try to limit myself to relatively few each year.

I had an outstanding experience at the Gothenburg competition since it felt more like an educational journey, and there was no excessive pressure to win. I have consistently attended and judged the Ettlingen competition for over 30 years and find it to be one of my favourites because of the impeccable standard and the fact that it is designed for young minds.

I specifically enjoy organisations that provide a nurturing environment for their candidates, regardless of their ages. Although the idea of a “competition” may seem incompatible with artistic expression, the music industry will always fabricate a highly competitive environment at the top. So, competitions, when well run should involve jury members who are specialists in their field and should be in the best position to help in the “selection process”. But as much as I love this format, there are aspects that I dislike. (But that is for another day!)

I have already mentioned that some of my students have flourished without partaking in significant competitions: Benjamin Grosvenor never competed after a junior UK BBC competition when he was 16; Yevgeny Sudbin seldom competed and Freddy Kempf only competed once. However, Jose Fegali and Anna Geniushene gained successes in The Cliburn which certainly was a different and instant path to establish a career.

Gradually building a reputation that experts recognize and promote is better than being a newly crowned monarch whose recognition ultimately fades away too quickly.

What always fascinated me is the sheer variety of music and people one encounters. For instance, I have participated on numerous occasions over the past three decades, including relatively modest ones for young students, and grand ones like Cliburn and Moscow. Each has its own charm. Take Gothenburg, for example – it’s a humbling and educational experience, characterized by sharing, playing, and talking with fellow musicians, minus the tension that usually accompanies such contests.

For me, the quality of care and attention that candidates receive counts a great deal in my evaluation of competitions. I find it reassuring to know that those vying for honours are given the necessary support to ease away from the overwhelming pressure to win. I am all too aware that competing can be a source of stress for many.

Patrick: As you mentioned, many aspiring musicians aim for a career on stage, often leading to competitions, conservatories, scholarships, and a professional career. Clearly, the moment of competing is always there within the profession. As someone with experience in this field, I want to discuss how competitions have evolved over the years. You’ve served on many juries throughout your career and have seen the changes firsthand. It seems that competitions are increasingly focused on education and building bridges between different approaches. Additionally, there appears to be a growing influence from Asia in the world of piano playing. Can you reflect on how competitions have transformed over the past 25 years or so?

Christopher: I don’t think that much has fundamentally changed in structure. They still do the same thing. A lot of competitions, they do a kind of lip service: you can talk to the jurors and get some feedback. I’m not cynical, I’m just sceptical about whether that is really a very valuable system. For a start, sometimes you have to do it as soon as you’re eliminated, and competitors are disappointed, they’re in no mood really to be told whether they were good or bad. And often the advice they receive from different jurors is more contradictory or confusing.

Some competitions do include master classes with members of the jury. That’s more to the point. And some combine the whole thing in a kind of festival atmosphere where everybody plays gets some concert opportunity. But the basic format of Moscow or The Cliburn or Chopin, I don’t think it’s changed, apart from the extraordinary proliferation of people who enter. I mean, for the last Cliburn, I think they had about 380 applications. It was cut down to like 150 or 160. I was at the pre-selection. We thengot it down to 72. And they were invited to play live in Fort Worth. And then they chose 30 or 32. So, even to get into these big competitions is almost impossible for most people.

I believe Ettlingen is an excellent illustration. I served on the jury for the first time back in the early 80s, almost four decades ago. Initially, it was a charming, modest competition largely featuring European participants. However, the competition underwent a significant transformation with the second edition taking place soon after the era of Perestroika. The number of applicants skyrocketed from around 80 or 100 to 280, prompting the introduction of a pre-selection process. With the Iron Curtain lifted, some 120 applicants from Russia were added to the mix.

It nearly broke the competition because they thus had to find massively more hospitality for applicants, many of whom had little money. But the competition survived. I think that was when we began to realize that every Russian pianist wasn’t a genius. Back then the Russians only let out the star players to take part in competitions. We then found out; “Yes, sir, we’ve got wonderful Russian players, but – as with British – there are some pretty bad ones as well!” And then, of course, came Asia, with massive entries from China, South Korea and Japan. The entry from China was enormously increased when Lang Lang won Ettlingen in 1993.

Suddenly, Lang Lang was the star pianist. Every Chinese mother dreamed of their child following in his footsteps, flocking to apply to competitions like Ettlingen and Warsaw. The technical prowess displayed, especially by the under 15s, was astounding. Yet, over time, the initial awe faded as a lack of depth, gravitas, personality, and intensity became apparent in many of the young performers. Nevertheless, the truly exceptional ones remained outstanding in their talent.

I believe that currently, some of the most exceptional players are from Asia; Japan was perhaps first to be known for producing competition winners, followed later by China and South Korea. However, it seems that Korean pianists are now dominating big competitions. That being said, there are incredible artists in every country. Even in European countries, there are exceptionally talented players, but there are always those few who stand out and captivate listeners with their exceptional artistry and imagination. As Neuhaus astutely points out, giving a meaningful lecture requires more than simply being able to enunciate words, and the same principle holds true for piano performance. It is not enough to just play the notes with technical precision, a truly great pianist must also possess an emotional depth and unique perspective that captures the audience’s attention and elevates the performance to something truly extraordinary.

Patrick: In a recent interview i did with Garrick Ohlsson, we delved into his victory at the 1970 Chopin Competition in Warsaw and the evolution of piano playing. Ohlsson noted that in the past, a pianist’s country of origin was easily identifiable through their playing style, but now it has become more difficult to discern. Is this shift towards a more internationalized approach to piano playing a positive progression, or does it risk diluting traditional styles?

Christopher: I absolutely agree there. I mean, in fact, that in the 70s, 80s, there was a definite and phenomenal Russian school. Of all them all, I think the most identifiable now is possibly still the French school. However, nowadays, piano playing has seen a diaspora of influences, and it’s become challenging to classify piano players based on their schools. I think schools of violin and string playing still exist rather more.

But piano playing, well, it’s just been such a diaspora, such a wide array of influences now. So, whether the schools are brought on by this influence or whether they’re corrupted by it, I don’t know. But there’s a kind of cross breeding because the great Russian teachers, a lot of them have been in the West. The great, wonderful Chinese teachers, they’ve nearly all studied in the West. Before, they’ve only studied in Moscow. And so, there is this cross fertilization.

So, the edges are blurred. I am not sure you can talk of an “Asian SCHOOL”. It has been developed by so many European and American influences. But they have taken such training to a really high level, and often not merely techinically. Perhaps I admire and identify most with the South Korean, because there is such a deep core of sound and seriousness. I certainly am not denigrating the others, but Chinese tend not to have that richness of sound and that kind of gravitas. But over long years of competition jury work I can find them just a little predictable. (Many clear exceptions of course!)

Patrick: The topic we are discussing is fascinating as it explores how narratives drive culture forward through time and their connection to the past. Sharing music and cultural norms globally naturally leads to different interpretations of narrative, drama, and gravity. What are the benefits of cultural exchange across borders, and how does culture perception vary between regions like Europe and China? Considering their different historical contexts, it is evident that diverse cultural perspectives exist.

Christopher: It is important to acknowledge the rich cultural heritage of Chinese music, Chinese opera, and folk opera. Just as Hungarians have a strong tradition of folk music and dance, and Italians have a deep-rooted culture of opera, we must not overlook these aspects of cultural identity. Although it is unclear what specific cultural traditions exist in England or Sweden, it is evident that where I teach, the Academy boasts a diverse group of talented pianists from various backgrounds. By welcoming these musicians and exchanging ideas with them, students have the opportunity to broaden their musical horizons and engage in a truly international dialogue. Music, being a universal language, has the power to bring people together and facilitate mutual understanding across cultures. This is part of the tragedy of Brexit: we can no longer attract the wonderful and diverse student population from Europe that was so stimulating.

Patrick: You have had many students during your career as an educator. Many are well-known names at the highest level. Many are surely very eager to hear about the methodology you use when teaching at the top level, so to speak. How do you develop someone who already has so much knowledge and a clear artistic profile?

Christopher: The more advanced the student and the more genuinely gifted, the less appropriate is what could be called “methodology”. Of course with younger or less musically developed pianists then indeed there is a certain “method”. But here surely we are dealing with especial and individual talent and to try to mould this into some pre-determined box seems a recipe for stultifying the very uniqueness of the student.

So one has to respect THEM and try above all not to risk suppressing their musical personality.

Of course this is NOT some invitation to musical anarchy: my role is to try to strike a balance between allowing the student enough free rein, but being there to put the brakes on – hard if necessary – if the individuality is at risk of misrepresenting the essence of the music they play. And increasingly as they become real performing artists, our sessions together are almost as much discussion as instruction.

Nothing gives me greater pleasure than when people remark how totally different Yevgeny Sudbin, Benjamin Grosvenor and Anna Geniushene sound!

Patrick: Can you describe the key aspects of piano playing and how to best develop these during a student’s years at the bachelor’s and graduate level at the Royal Academy where you have been teaching all these years?

Christopher: This question surely needs almost a whole book.

Perhaps, though, one can start with the fact that piano playing cannot be totally divorced from music. So the stronger the musical image the more clearly the student can work at the pianism demanded to meet this image.

And I think we can almost begin with the idea of SOUND. If the ear is not really functional then any work risks being merely motoric. Learning almost every other instrument starts with the difficulty of actually producing an acceptable sound, but this can seem all too easy for pianists! You press a key and – magic – you have a musical sound! (Of a type!)

We talk glibly about “technique” so much, but can forget that the Greek origins of that word mean “pertaining to art/skilful”.

But to try to answer about how to teach key aspects of playing the piano in a paragraph is almost an insult to the thought and work that needs to go into this.

Patrick: You have conducted masterclasses all over the world. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this teaching format?

Christopher: I enjoy giving masterclasses: hearing new young musicians and having to respond on the spot both to them as individuals and to music that on occasion I may simply never have heard. (It is far from uncommon to come to give such a class with absolutely no foreknowledge of the repertoire you are to hear!)

But I sometimes describe this as “teaching without responsibility”, in that – although one approaches the task extremely seriously and hopes to be helpful, at the end of the day the student goes away and probably that is the end of your musical connection. It is the opposite of regular teaching and mentoring where you feel a real duty to nurture the student through a period often of several years. This, of course, is by far the more essential and valuable stimulus to the development of the student.

But at best masterclasses can be a real source of inspiration and a valuable opportunity to get a new pair of ears and a new musical mind to hear and advise you. I remember perhaps the most consistently great masterclass teaching I ever heard, given by a great musician (and a fine man) – Alexander Satz – who left Russia after perestroika and settled in Graz. He was our Visiting Professor of Piano for many years and I have seen students after his lesson seeming almost to walk on air, they were so inspired. And his lessons were totally without any self-aggrandisement – just a sense of humility in front of great music.

There are risks – not least that the student feels this teacher is on a higher pedestal than his regular teacher and that all he suggests has to be suitable advice that he MUST follow, (and even perhaps that his regular teacher is not due equal respect).

And the worst misuse of the system I came across was on a summer course where one student played the same work to three or four different masterclass teachers in succession. Madness! Finally I would have to say that I do not think any teacher in a public masterclass should ever humiliate any student.

Patrick: During my recent visit to Cremona, I attended one of the 180 events happening over the course of three days. This particular event was a panel discussion on the topic of Erasmus and beyond. It was a stimulating conversation with speakers from seven countries, including the United States. I’m curious; how has the EU’s Erasmus program been utilized and impacted internationalization, both before and after Brexit?

Christopher: I mean for music education and education generally, and the sciences too, apart from anything else, Brexit’s been an absolute disaster. We are no longer in Erasmus. If a European student wants to come to us, the fees are astronomically high. They pay the same as in America or as Chinese students. They used to pay the same as an English. So, if they’re going to come we – the Academy – have to fund them basically.

If a talented student from Sweden or Italy comes to study as an undergraduate, we are seeking a 4-year course and funding of £120,000 for them. This is a reality we must confront. We used to have several students come through Erasmus, often in their third year of study, with many returning after completing their bachelors for postgraduate studies.

We have in the past had exchanges for teachers and students with institutions in many European countries. I visited many institutions myself, though I found this not to be as productive as I had hoped. Teacher exchanges, while interesting, may not be the most fruitful use of time and resources. However, the opportunity to exchange students for a semester or a year can have a significant and positive impact.

Patrick: Have there been created any substitute exchange programs after Brexit?

Christopher: We currently do not have any concrete exchange programs in place. While we have connections with various conservatoires and universities, there have not been any official exchange programs established. There was one individual who came two years ago, but that was shortly after Brexit and regulations were still in flux. It is now clear that Brexit has brought an end to any potential collaborations. So very sad.

Patrick: What is coming up in your busy and evidently non-retired life Christopher?

Christopher: If my health is good, and my wife’s health is good, I think we both like to go on doing what we do. But gradually, I guess things will reduce a little. My wife keeps telling me I’m unable to say no… I think my early upbringing made me believe I’d never be good enough to earn a living playing the piano. So, I still have this deep rooted slight anxiety: “I ‘d better take it because I might never be asked again”!

So, maybe I am turning down a few more things, not because they’re lesser or because they pay less, but because I just realized I’ve got to say no a bit more. Now, I’d like to carry on teaching at the Academy, as long as people want to study with me and the Academy want me to teach. But I think I’m going to want to reduce by a few hours a week – instead of which this last year it went up by 5. And that’s not what I wanted. And the mix of external work such as juries and masterclass courses is a refreshing and different experience.

The post Master Teacher Christopher Elton – Never Ending Impetus appeared first on Piano Street Magazine.

from Piano Street Magazine https://www.pianostreet.com/blog/articles/master-teacher-christopher-elton-never-ending-impetus-12850/

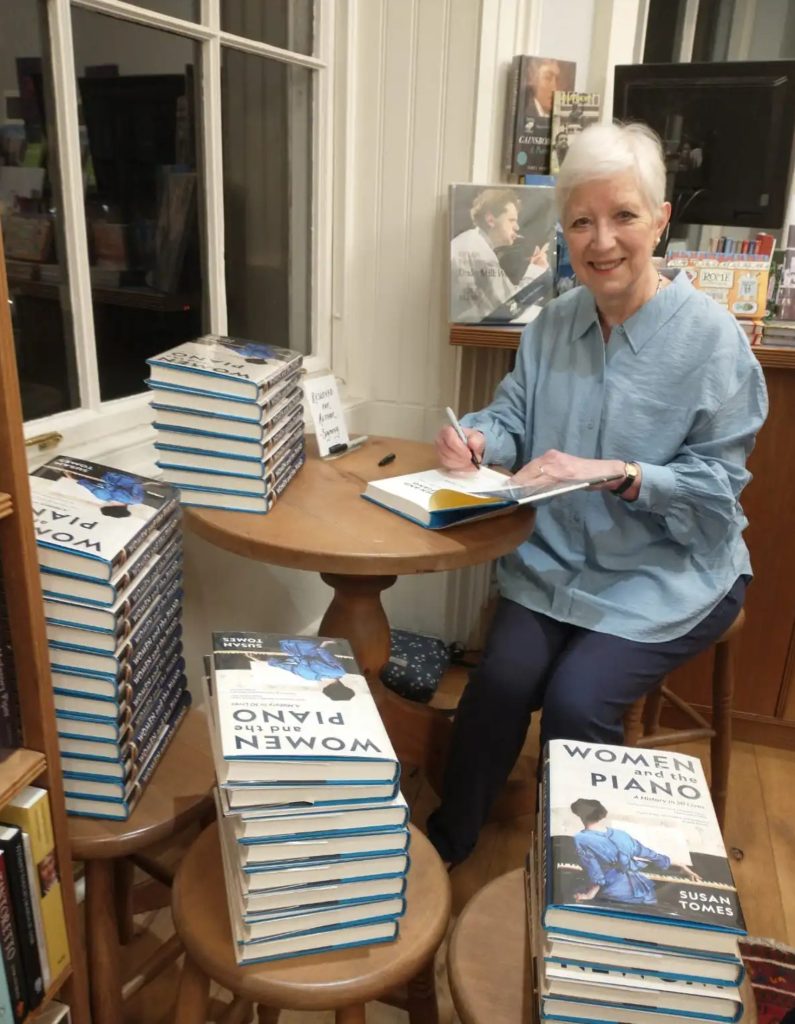

Piano Street: Dear Susan, we were so happy to talk with you after the release of your book “The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces” back in 2021, and just recently your latest oeuvre was published; ”Women and the Piano”. This is your seventh book and this makes us wonder why writing about music is so important for you?

Piano Street: Dear Susan, we were so happy to talk with you after the release of your book “The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces” back in 2021, and just recently your latest oeuvre was published; ”Women and the Piano”. This is your seventh book and this makes us wonder why writing about music is so important for you? PS: In the course of your research, we imagine you’ve encountered a vast array of repertoire. Music history has traditionally been written from a perspective that elevates certain titans of style as the reference point and definition of their era. Meanwhile, numerous composers and artists have been working on their own unique paths, often unnoticed and marginalized by the historical record. Which female composers or artists did you find particularly stood out in this sense, carving their own distinct trajectories despite the prevailing narrative?

PS: In the course of your research, we imagine you’ve encountered a vast array of repertoire. Music history has traditionally been written from a perspective that elevates certain titans of style as the reference point and definition of their era. Meanwhile, numerous composers and artists have been working on their own unique paths, often unnoticed and marginalized by the historical record. Which female composers or artists did you find particularly stood out in this sense, carving their own distinct trajectories despite the prevailing narrative?

Horowitz used to study all the piano works by a given composer even if, as in the case of Fauré, he only included two pieces in his concert repertoire. Does your perspective change when you have an overview of the entire body of work?

Horowitz used to study all the piano works by a given composer even if, as in the case of Fauré, he only included two pieces in his concert repertoire. Does your perspective change when you have an overview of the entire body of work?

The music of Prokofiev follows its own, sometimes quite unpredictable logic, while at the same time being full of references to the Classical and Romantic eras. He seems to have always retained something of the fearless, playful, even arrogant approach he displayed as a child. For example, the young Prokofiev refused to touch the black keys, and so wrote a piece in “F major” but without the customary B-flat. At age five, he also composed a “Liszt Rhapsody” on a stave with nine lines and without bars, prompting his mother to give him “a more systematic explanation of the principles of musical notation.”

The music of Prokofiev follows its own, sometimes quite unpredictable logic, while at the same time being full of references to the Classical and Romantic eras. He seems to have always retained something of the fearless, playful, even arrogant approach he displayed as a child. For example, the young Prokofiev refused to touch the black keys, and so wrote a piece in “F major” but without the customary B-flat. At age five, he also composed a “Liszt Rhapsody” on a stave with nine lines and without bars, prompting his mother to give him “a more systematic explanation of the principles of musical notation.”